Bain’s decision to formalize partnerships with seven major venture firms managing roughly $190 billion in assets is less a breakthrough than a recognition of how the market already works. Consultancies have long helped large enterprises navigate startup ecosystems, but the move signals something deeper: traditional corporate innovation structures are no longer keeping pace with the speed of AI development.

This development raises a simple question with meaningful implications. If the startup ecosystem is more open and transparent than ever—demo days are streamed, founders post roadmaps publicly, and investor updates circulate widely—why do corporations still need intermediaries to find and evaluate emerging technologies? The answer is not in access but in capacity. Bain’s announcement reflects a structural shift in how enterprises digest innovation, revealing a widening gap between what companies can theoretically access and what they can practically absorb.

The emergence of consulting-VC alliances is rooted in a familiar tension. Large enterprises talk about transformation but frequently struggle to operationalize it. AI has amplified this divide. Inside many corporations, innovation programs coexist with layers of governance, entrenched incentives, and risk-averse decision-making. These dynamics slow down adoption even when executive intent is high.

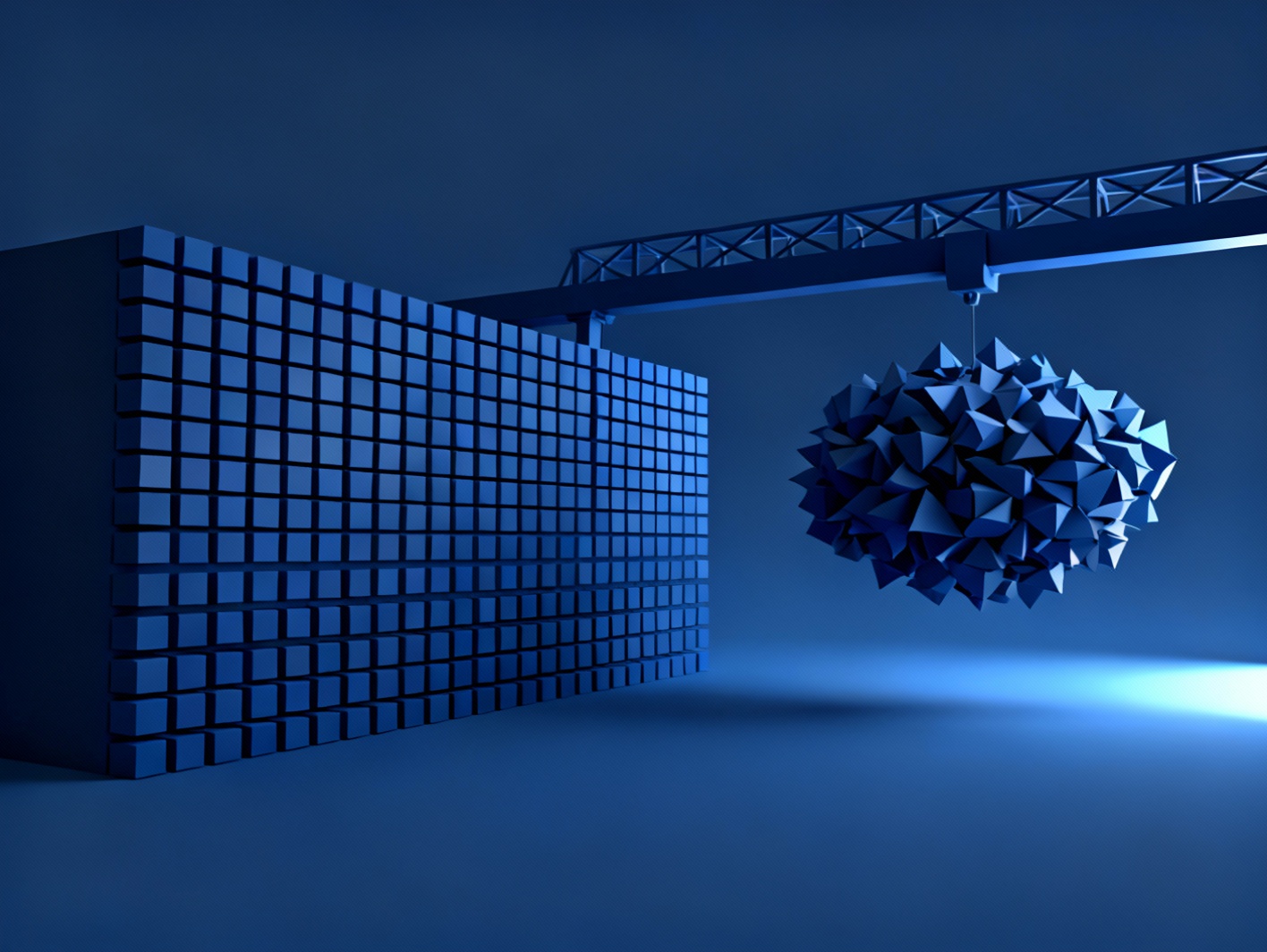

The result is often innovation theater—hackathons, pilot programs, and task forces that generate activity without shifting the operating model. The common narrative blames a “discovery problem,” implying that enterprises can’t find the right startups. But the real issue is the organizational machinery required to evaluate, pilot, and integrate new technology at anything resembling startup velocity. Identifying promising AI companies is easy. Running responsible, cross-functional pilots with clear ROI is not.

Bain’s track record highlights this disconnect. Since 2017, the firm has facilitated more than 250 executive immersions and over 3,000 curated connections between corporations and startups. These numbers illustrate demand at scale: enterprises are paying to outsource not just identification but translation—turning startup potential into enterprise-ready action.

Building internal relationships with VCs is theoretically possible. In practice, it is costly, slow, and dependent on talent that many corporates struggle to recruit or retain. For executives under pressure to show progress on AI strategy, paying consultants for structured access becomes a pragmatic shortcut, even if it doesn’t resolve the deeper organizational frictions that impede implementation.

The alliances are not simply advisory enhancements; they are reciprocal market plays shaped by incentives on both sides. For venture firms, the value proposition is clear. Enterprise sales remains one of the toughest growth levers for early-stage companies. Many lack dedicated business development teams or the network density required to reach corporate buyers. Bain’s relationships with large enterprises offer a scalable distribution channel for portfolio companies.

Comments from Menlo Ventures underscore the point: this is portfolio value creation, not ecosystem altruism. By embedding themselves into enterprise transformation agendas, VCs can accelerate adoption for startups that otherwise face long, multi-stakeholder sales cycles.

Consultancies, meanwhile, are defending their strategic relevance. The AI era has intensified competition from specialized implementation firms, cloud hyperscalers, and big tech consultancies that package strategy and execution in a single offering. Formalizing VC partnerships helps Bain reinforce its position as a trusted navigator of technology flux—one capable of curating, vetting, and orchestrating solutions from a rapidly shifting AI landscape.

The specific VCs involved—Bain Capital Ventures, Battery, ICONIQ, Insight, Lightspeed, Menlo, and NEA—are also telling. They represent deep coverage across foundational models, data infrastructure, and applied AI. Their public association with early bets like OpenAI, Anthropic, Mistral, and Databricks provides signaling power, though most enterprise use cases still hinge on integration and application layers rather than foundation models themselves.

Viewed through an investor lens, the structure resembles a two-sided market: consultancies monetize enterprise demand for guidance, VCs gain guided access to buyers, and enterprises use the alliance as a risk-managed on-ramp to emerging technology.

For corporate leaders, the appeal of consultancy-led curation is understandable. It lowers risk, compresses search costs, and externalizes early filtering. But it also creates dependency. As AI adoption accelerates, enterprises may need to build more direct relationships with venture firms to expand their field of view beyond what consultants curate. This is especially important for companies seeking exposure to unconventional or frontier technologies that fall outside standardized playbooks.

Investors in enterprise AI should view these alliances as emerging distribution infrastructure. A startup plugged into a consultancy’s enterprise transformation pipeline may have a materially shorter path to revenue. Evaluating whether a portfolio company has, or should pursue, similar partnerships is becoming part of diligence.

Founders, meanwhile, face a new calculus in fundraising. Being part of a top-tier VC portfolio may now come bundled with structured enterprise access, changing the strategic value of lead investors. The question shifts from “Who can help us raise the next round?” to “Who can get us in front of the right enterprise buyers?”

The broader trend is clear. As the gap between frontier AI development and enterprise adoption widens, intermediaries will proliferate. That includes consultancies, systems integrators, and venture firms aligning more tightly to shape market access and influence purchasing decisions.

Executives should also monitor potential conflicts. Bain has a growing 1,500-person AI team building its own products and tools. When consultancies act as both evaluators and creators, the line between objective advice and commercial interest can blur. Knowing when to rely on intermediaries—and when to diversify inputs—will be a strategic differentiator for enterprises aiming to stay competitive.