Venture capital’s retreat from consumer hardware is no longer a cyclical slowdown but a structural reallocation of capital. Over the past several years, funding to consumer-facing product startups has contracted across nearly every major category, from direct-to-consumer brands to premium electronics. Investors have watched margin pressure, supply chain volatility, and inconsistent exit outcomes compound into a weaker return profile relative to software-driven sectors.

The challenge is rooted in performance. Fashion labels, connected devices, and household gadgets have struggled to generate dependable outcomes at scale, leaving limited evidence that category growth translates into investor returns. Even in periods of strong consumer enthusiasm, many of these businesses delivered modest margins, required heavy working capital, and failed to sustain defensible competitive positions.

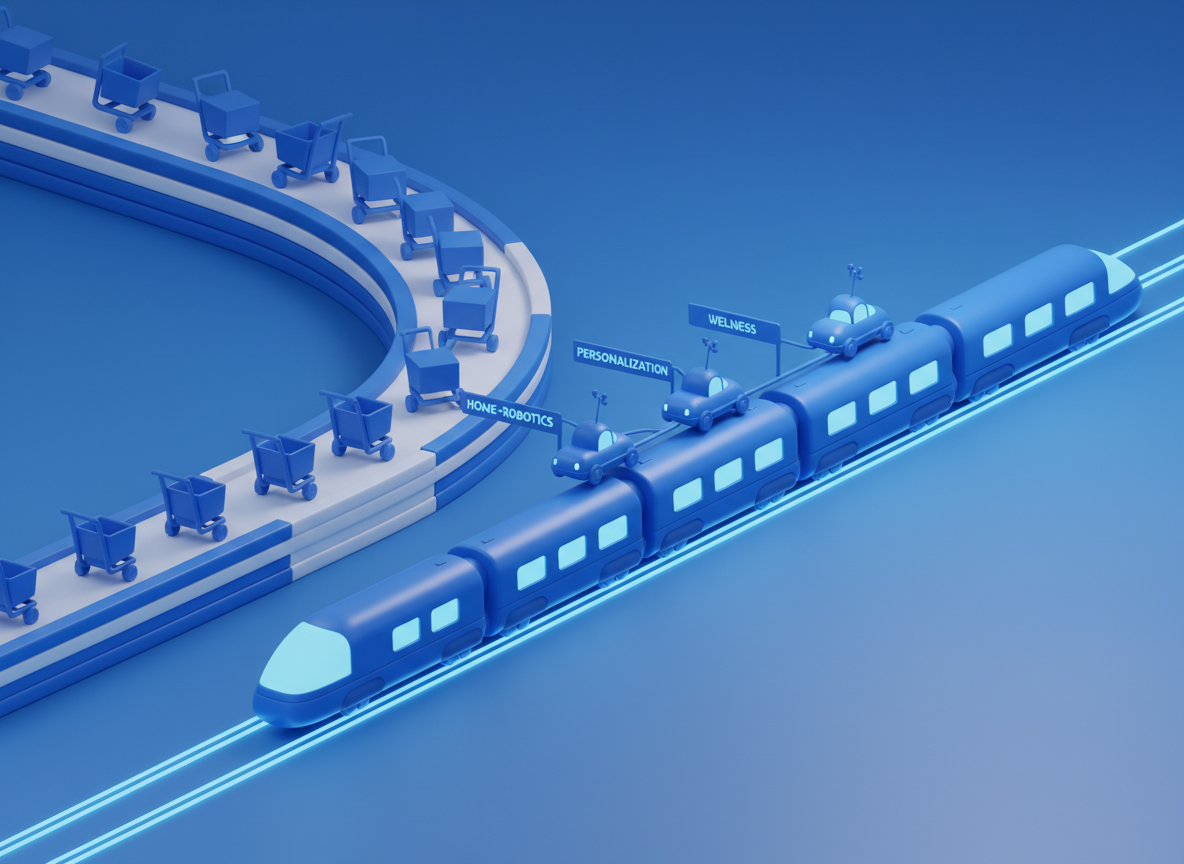

This contraction matters strategically. As capital concentrates in AI and enterprise software, investors risk overlooking sub‑segments of the consumer landscape where defensibility is strengthening and business model innovation is addressing old weaknesses. Understanding where funding has evaporated—and where it is quietly returning—creates a more nuanced picture for allocation decisions.

Despite the broader pullback, select categories are still attracting nine‑figure rounds. Wellness technology, data‑driven personalization, and robotics‑enabled consumer solutions demonstrate that investor appetite has not disappeared; it has simply become more selective. These exceptions point to where durable value may still emerge in an otherwise challenging environment.

Consumer hardware has struggled to compete with software and AI on core investment metrics. Manufacturing-driven businesses demand high upfront capital, carry lower margin ceilings, and require inventory and supply chain infrastructure that slow iteration. In contrast, software scales with near-zero marginal cost and offers gross margins that routinely exceed 80 percent. For funds managing liquidity expectations and compression across multiple vintages, the comparison has been unfavorable.

The structural challenges compound these pressures. Consumer hardware companies face production delays, quality-control issues, and complex logistics that weaken operating leverage. Competitive moats tend to be thin: once an idea gains traction, global manufacturers can replicate features quickly and at lower cost. Even differentiated brands struggle to defend pricing power as copycats proliferate.

High-profile failures intensified skepticism. Premium juicers, smart coolers, and over-engineered appliances raised substantial capital but failed to demonstrate sustainable demand or justify valuations. These outcomes eroded confidence among LPs who were already questioning the category’s capital efficiency. In parallel, the DTC boom revealed the fragility of consumer acquisition economics. CAC rose sharply, LTV underperformed projections, and the paid-social arbitrage that once supported rapid scaling collapsed.

Exit dynamics further discouraged participation. While AI and enterprise software saw expanding multiples and strategic buyers willing to pay for technology and distribution leverage, consumer hardware exits remained infrequent and modest. Acquisition candidates often valued physical products only marginally higher than cost of goods, leaving little upside for equity holders. Venture capital, which relies on outsized liquidity events to drive fund performance, found fewer paths to meaningful outcomes.

Together, these factors explain the sustained retreat. Investors did not abandon consumer products because of temporary market softness; they moved capital toward categories with superior economics, clearer defensibility, and more reliable exit prospects.

Health and wellness technology has emerged as a notable exception in an otherwise constrained consumer landscape. Investors continue to back companies whose hardware acts as a gateway to valuable biometric data, recurring services, and medically adjacent offerings. These dynamics shift the model away from one‑time product sales and toward ongoing engagement with compounding value.

Oura’s funding trajectory illustrates this shift. As a smart wearable with meaningful biometric insights, Oura built defensibility not through hardware innovation alone but through data accumulation and analytics. The device becomes more valuable the longer a user stays engaged, creating switching costs and enabling subscription‑based revenue. This model aligns more closely with enterprise SaaS economics than with traditional gadget businesses.

Eight Sleep’s $100 million Series D underscores the same pattern. The company pairs a high‑end sleep system with ongoing software services and physiological monitoring. Investors view this hybrid model as a path to higher lifetime value and improved predictability, addressing the margin constraints that historically plagued consumer hardware.

Demographic shifts are creating parallel opportunities in longevity and menopause-focused wellness. Brands such as OneSkin and Womaness target aging populations whose spending power is increasing and whose needs remain underserved. These companies leverage scientific positioning, personalization, and emotional resonance to build differentiation in categories historically defined by commoditized products.

The question remains whether wellness tech truly solves the return problem or merely postpones familiar challenges. While data moats and subscription layers increase defensibility, these companies still face hardware complexity, regulatory nuances, and the need for sustained consumer engagement. For now, the sector continues to command investor attention because it offers a credible path to recurring revenue and stronger margins than traditional consumer devices.

Personalization startups pitch themselves as the antidote to inventory risk, promising made‑to‑order models and AI‑driven customization that reduce working capital needs. From Arcade’s AI jewelry design to Blank Beauty’s custom nail polish and EufyMake’s 3D printing, these companies argue that manufacturing innovation creates a more efficient consumer business.

The core question is whether on‑demand production materially improves unit economics. In theory, producing only what is sold eliminates overstock and discounting. In practice, it often shifts complexity upstream. Customization requires flexible manufacturing, specialized inputs, and slower throughput—all of which can raise COGS and limit economies of scale. Investors evaluating these businesses must determine whether improved margins are real or a temporary artifact of early-stage enthusiasm.

AI plays a central role in the personalization thesis. As tools become better at designing, recommending, and adjusting products, customization could reach economic viability at higher volumes. Yet AI does not solve every bottleneck. Physical production still requires labor, materials, and quality control that scale differently from digital goods.

Market size is another constraint. Even well-executed personalization models may face narrower TAMs than mass-consumer brands, limiting venture-scale outcomes. Made‑to‑order companies also need significant capital to build manufacturing capacity and achieve reliable throughput, extending the timeline to profitability.

For investors, personalization remains a nuanced opportunity. It offers pathways to differentiated products and reduced inventory risk, but the operational burden and TAM limitations require disciplined underwriting.

Some consumer companies continue to attract substantial capital despite the sector’s broader challenges, largely due to distribution advantages rather than product breakthroughs. Skims is the most prominent example. Its $225 million raise was driven not only by category growth in shapewear but by the powerful customer acquisition economics unlocked by celebrity reach. When a brand can drive awareness and conversion organically, it reduces dependency on paid channels and increases margin leverage.

Vivrelle demonstrates a different value proposition: subscription-based access to luxury goods. Its $62 million round reflects investor interest in business models that arbitrage ownership and rental economics, backed by predictable recurring revenue. The model depends less on product differentiation and more on inventory management and consumer affinity for flexible consumption.

These successes, however, remain outliers. Celebrity or community-driven momentum is difficult to replicate without unique founder advantages. For many startups, attempting to mimic these playbooks results in high marketing spend, uneven traction, and limited defensibility.

Exit prospects for branded consumer businesses also differ from technology-driven categories. Acquirers may value brand equity and distribution but often assign modest multiples compared to software or AI companies. Investors must distinguish between standout brands with structural advantages and the broader universe of commodity consumer products.

Consumer robotics stands apart from traditional product categories because it combines hardware, software, and artificial intelligence in ways that can create meaningful defensibility. Capital inflows reflect this belief. The Bot Co.’s $300 million raise, along with Benchmark’s backing of Sunday, signals investor conviction that household automation may represent the next major consumer platform.

Robotics attracts interest for several reasons. First, the underlying technologies—AI models, computer vision, and robotic manipulation—are advancing rapidly. Second, consumer willingness to adopt automation in the home is increasing, creating opportunities for recurring service models. Third, robotics companies often have IP-based moats that resemble advanced technology firms more than traditional appliance makers.

The convergence of AI and robotics is key. For these companies to justify valuations, perception, planning, and manipulation systems must improve to the point where robots perform tasks reliably and safely in unstructured environments. This requires significant R&D investment and long development timelines, which influence fund lifecycle expectations.

Commercialization remains uncertain. Bringing consumer robots to market involves not only technical breakthroughs but customer education, regulatory compliance, and post-launch servicing. Revenue may take years to materialize, testing investor patience and increasing capital demands.

Still, robotics represents one of the few consumer categories with a credible pathway to platform-scale value. Whether it becomes a durable investment segment or the next hype cycle will depend on execution, technological readiness, and timing relative to fund horizons.

The dominance of AI in venture funding reallocates attention and capital away from consumer products. For investors, the question is not whether the consumer category will regain its former scale but which sub‑segments justify focused attention within a more selective environment.

Three areas stand out as investable: data‑driven wellness, AI‑enabled manufacturing, and robotics-first approaches. Each offers a path to defensibility that aligns more closely with venture economics, whether through recurring software revenue, proprietary data assets, or technological IP.

Deal evaluation requires heightened scrutiny. Investors should prioritize companies with:

Position sizing matters. Consumer bets should occupy smaller portions of a portfolio unless tied to significant IP or platform potential. Reserve strategies must account for longer hardware cycles and the possibility of uneven early adoption.

The exit environment remains the most complex variable. Strategic acquirers buy consumer hardware companies selectively and typically at lower multiples than technology firms. Private equity may provide alternative liquidity, but often at valuations that require disciplined early-stage pricing.

A recovery in consumer investment would likely require improvements in acquisition economics, lower supply chain volatility, or new categories that deliver defensibility absent in traditional hardware. Alternatively, continued contraction may push innovation toward niches where data, automation, or health adjacency create more predictable value.

For now, the path forward is selective participation. Investors who understand where defensibility is strengthening—and where risks remain irreducible—will be best positioned to deploy capital in a category undergoing structural realignment.